Dr Guy Collender from the Centre for Port Cities and Maritime Cultures charts our changing relationship with the oceans

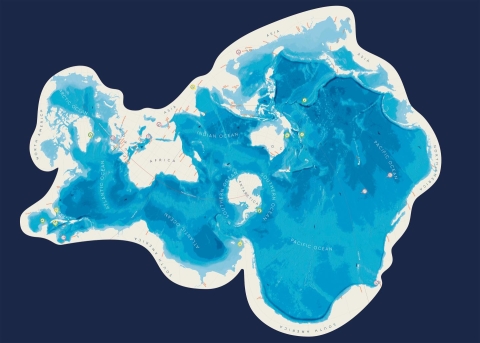

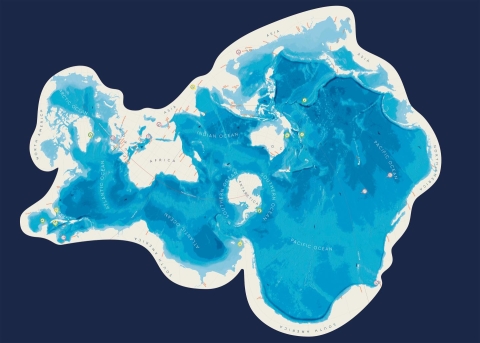

It initially doesn’t look right, but that’s only because it’s an unfamiliar perspective. The Spilhaus Projection (shown above) is an accurate representation of the world, but it just emphasises how the globe is dominated by water, not land. A gigantic version of this ocean map of the world, developed by South African-American oceanographer Athelstan Spilhaus in 1942, will be unveiled at the National Maritime Museum in London on 7 June to celebrate the UN’s World Oceans Day the following day. The extraordinary 400 square metre floor map will be the centrepiece of the new Ocean Court, and the public will be able to walk across this ‘map of the world according to fish’.

It is not just the Spilhaus Projection that is encouraging us to think more deeply about the 71 per cent of the world that is ocean. Filmmakers and policymakers are rightfully devoting more attention to the ocean. Public concern is also growing after decades of declining knowledge about the marine and maritime world from the mid-20th century onwards. At this point, it’s worth reiterating the collapse in the number of navy personnel, fishers, and dockers after World War Two as it underscores how society became less familiar with the ocean. The size of the Royal Navy peaked in 1944 with 864,000 personnel; it now has around 30,000 personnel. The UK’s number of fishers has fallen by 48% from 1995 to 2022 (from nearly 20,000 to around 10,000). The number of registered dockers in the UK has been estimated at more than 80,000 in the early 1950s and 10,000 by 2016. As people no longer worked at sea, or loaded and unloaded goods travelling by sea, they and their families and communities became less connected to the sea as a way of life.

Today, however, the tide is turning as the public is becoming more connected with the ocean again. Much of the credit for the turnaround and our renewed interest in the ocean should be given to the celebrated naturalist and broadcaster David Attenborough. His Blue Planet documentaries were pioneering, and the first episode of the second series in 2017 attracted 14.1 million viewers, making it the most popular British TV programme that year. His powerful new film Ocean shows how marine habitats and wildlife are being destroyed by industrial fishing, particularly dragging heavy nets along the seabed - a practice known as bottom trawling. The footage shows how international trawlers are outcompeting traditional fishing communities and nature as these floating factories engage in a modern form of colonialism at sea. However, despite such environmental degradation, Attenborough remains optimistic as the marine environment can ‘bounce back’ remarkably quickly if left alone, as shown by the success of fishing-free marine reserves, including Papahānaumokuākea, near Hawaii. The film implores policymakers to take action and make history by protecting our waters at the UN’s Ocean Conference in Nice from 9-13 June. As Attenborough says in the closing line of the film: ‘If we save the sea, we save our world’. Such campaigning zeal is resonating with the public. My first attempt to see the film on its opening night was foiled because it was sold out, and when I did see it days later the cinema audience responded with a round of applause at the end of the film.

Momentum is undoubtedly building to protect our marine environments, and hopefully decisive action will be taken at the UN’s upcoming Ocean Conference in Nice. This will be a logical extension of existing initiatives and commitments. In 2015, the UN agreed the Sustainable Development Goals, with goal 14 dedicated to conserving and sustainably using the ‘oceans, seas and marine resources’. We are in the middle of the UN’s Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development (2021-2030). Ocean Literacy is also gaining credence as a term. It refers to understanding human impact upon the ocean, and the impact of the ocean upon our lives and wellbeing.

Such environmental concerns also include pollution from shipping, which currently accounts for three per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions. There is growing interest in the shift from carbon-based fuels to green technologies, and there are a number of options available, including the use of methanol, ammonia, and even the partial reintroduction of wind power.

Academics at the Centre for Port Cities and Maritime Cultures at the University of Portsmouth are researching the sail to steam transition in the nineteenth century to learn the lessons for the transition from carbon to green today. Four PhD students and post-doctoral researchers will be recruited as part of the Sail to Steam, Carbon to Green project, which is funded by Lloyd's Register Foundation. They will research how coastal communities in the Global South were impacted by the sail to steam transition, and how the move from fossil fuels to carbon-neutral shipping will impact the same communities today and in the future. The first three-year phase of the project will focus on Macau in China and Callao in Peru.

The focus on the ocean is welcome, but it also needs to extend beyond marine wildlife to health and safety at sea, and the coastal communities often left behind when our seas are damaged. Global supply chains dependent upon ocean-going trade continue to pose risks to seafarers and others, as well as economic disruption. Stuck in the Suez Canal in 2021, the Ever Given - a giant container ship - paralysed shipping for six years. One person died in the salvage operation. Last year the Dali - another giant container ship - brought down the Francis Scott Key bridge near the US city of Baltimore, with the loss of six lives. In March this year a cargo ship and oil tanker collided in the North Sea about 12 miles off the UK’s coast near East Yorkshire, leaving one man dead. UK seaside cities have also been neglected for decades, and often suffer from deprivation, poor health outcomes and limited prospects. Our research at the University of Portsmouth’s Centre for Port Cities and Maritime Cultures is addressing these challenges by analysing the past, present and future importance of urban-maritime cultures across the globe.